The Development of a Mass Visual Culture in American Society, and its grounding and enlivening effects in the reaffirmation of the mythos and social imaginary of the American populous

Thanks to the efficiency of production and the massively economical nature of its distribution, lithography took America by storm in the 19th Century, nestling itself into a vast range of applications in art, commerce, and advertisement. Though there were many printmaking firms in operation at this time, none have stood the test of time as fortuitously as Currier & Ives (1835-1907). the firm called itself "the Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints'' and advertised its lithographs as "colored engravings for the people"—Currier & Ives effectively managed to streamline production to such an extent that, over the course of their 70-year career, over 7500 original lithograph prints were brought to market, the prints produced and sold in unlimited editions, amassing to estimates of well over one million total prints put into circulation. More essentially, a Currier & Ives print was sold for no more than a few dollars, from the beginning of their printing career up until the very end.

Currier & Ives found their start in the economic uncertainty and technological catastrophe of the 1830s, a series of large-scale calamities that unsettled Americans and created deep, lingering insecurities in the American social imaginary; a sensibility comprised of a stubborn faith in progress above-all-else and an oft-professed determination to overcome adversity. The 1830s saw the initial developments of the market for self-help and advice manuals, alongside which the lithograph prints of Currier & Ives and their contemporaries aided the American masses in reaffirming a national identity, a sense of self in the face of uncertain fate, by way of imagery and imaginative space that in a cathartic manner served to voice widespread fears, hopes, ideals, and entirely American victories and pleasures.

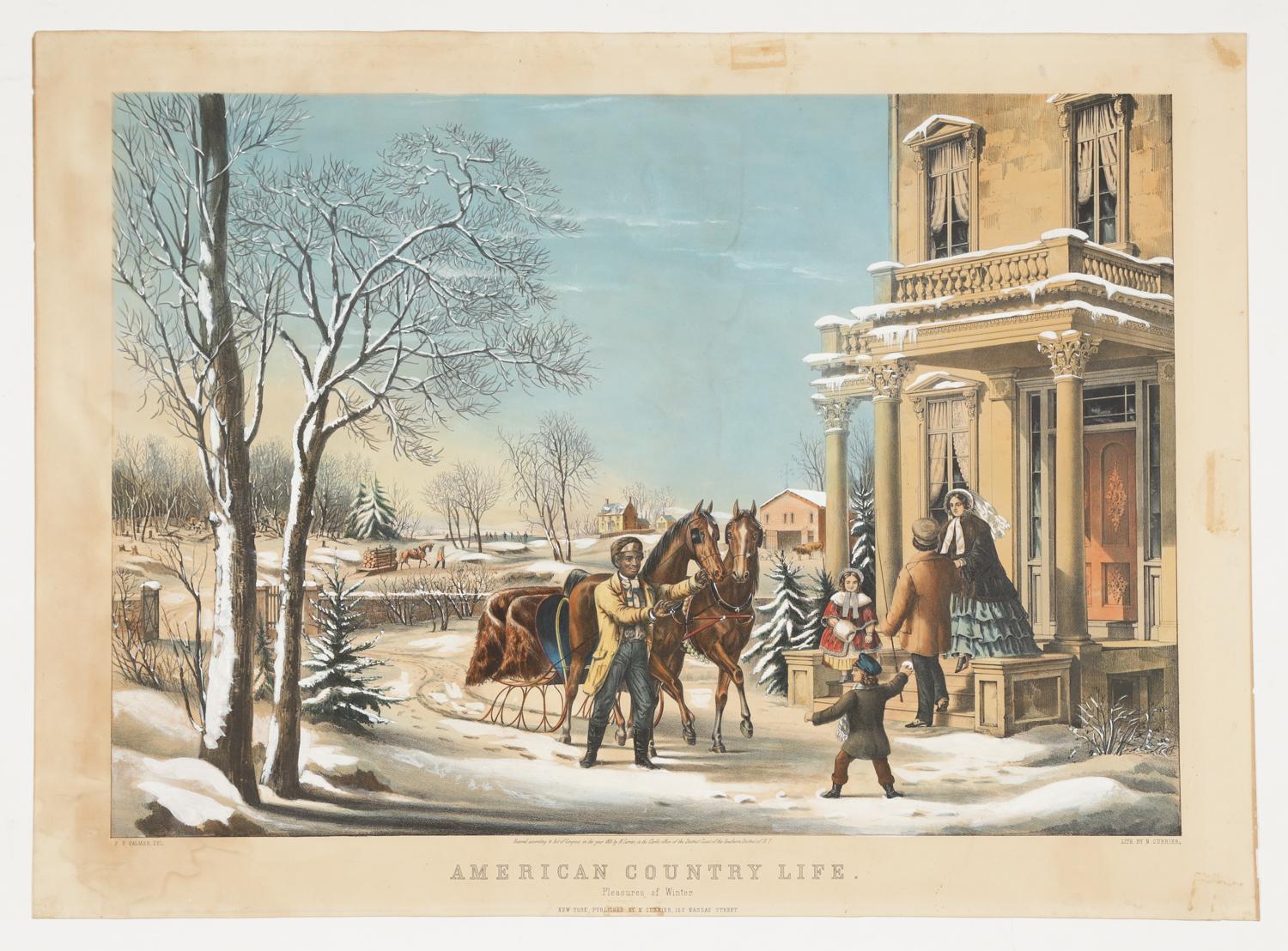

Whether it was the warm, comforting simplicity of the bucolic scenes of everyday American life (American Country Life, Pleasures of Winter, Litho, 1855),

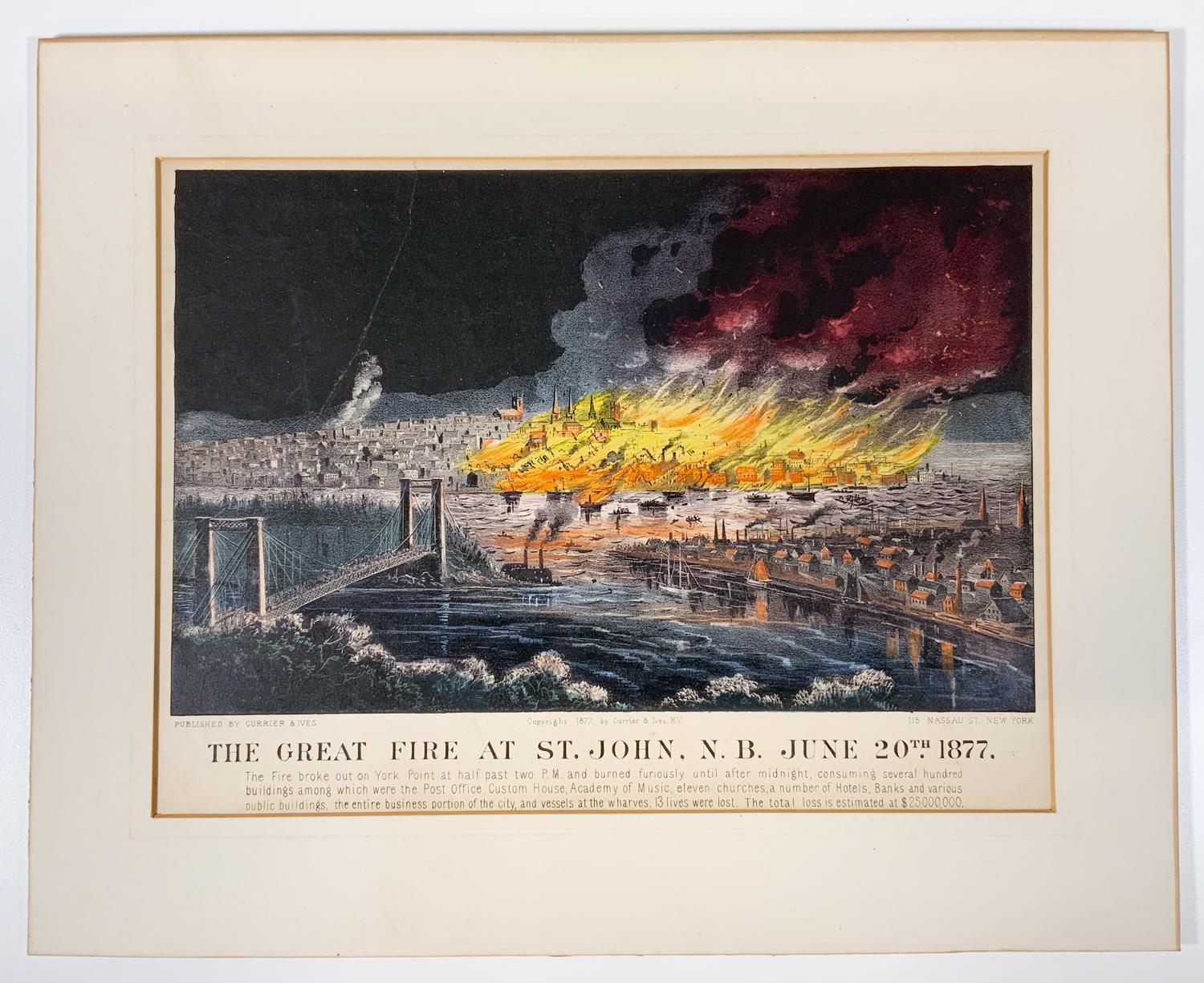

the sensitively, emotionally memorialized representations of contemporary disasters (A The Great Fire at St John, NB June 20, 1877),

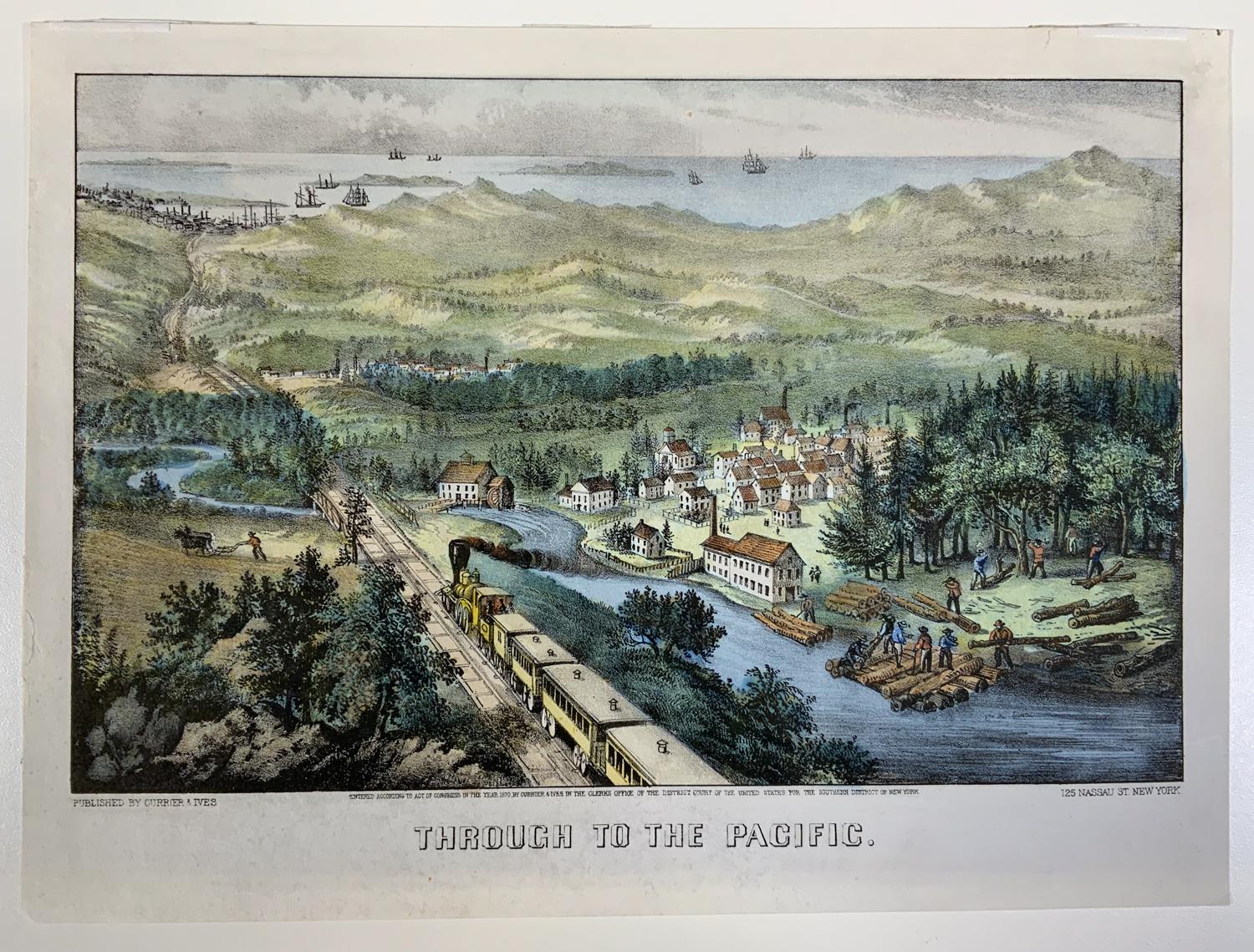

or the freedom-laden, youthful opportunity expressing portrayals of the frontier and American Manifest Destiny (Across the Continent),

the visual culture formed and promulgated—even though it is a mythical vantage, not necessarily linked to a real lived American reality—by way of lithograph prints in 19th century America served to vividly enliven and reaffirm the righteousness of American identity and all that it entailed; the prints thusly best understood as compositions combining memory, myth, and progress-oriented hopes of a nation that had been shaken to its core, but refused to fall into the annals of history.