Chinese Bronzes range from simple, almost utilitarian to whimsical pieces whose decoration far surpasses their use. The rhinoceros-shaped Han Dynasty gold-and-silver-wire inlaid bronze zun-form vessel is one such fantastic object. At their time of creation, these were owned and used by the elite of China’s ruling classes. Now these fantastic works are open to viewing by all who revel in the fantastic nature of this archaic Chinese art form.

The first bronze articles were produced in China around 2000 BC. China’s Bronze Age is generally associated with the Shang Dynasty (1600-1050 BC) and the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BC). Since that time these same forms have been repeated finding new life in various media.

Ancient bronzes served many purposes in rituals, court life, and daily life. Their form was generally speaking decided by their function and there were specific forms for specific purposes. These forms had various characteristics and decorative elements, some were incredibly finely cast and others more roughly so. Outlined here are a few of those forms.

Gu are slender vessels, used as to drink wine or as ritual wine vessels. With a slightly flared base and wide top, they are commonly seen in square form as well as round. At the center of the body there is often a bulb that protrudes slightly.

These three-legged vessels were used to hold wine for ritual purposes. They have a distinctive shape, with an elongated spout and generally also with a handle. One example in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum is thought to be manufactured from sheet metal. Most often Jue is not thin but of a similar thickness to that exhibited here from the Shanghai Museum of Art. This example dates to the early Western Zhou Dynasty.

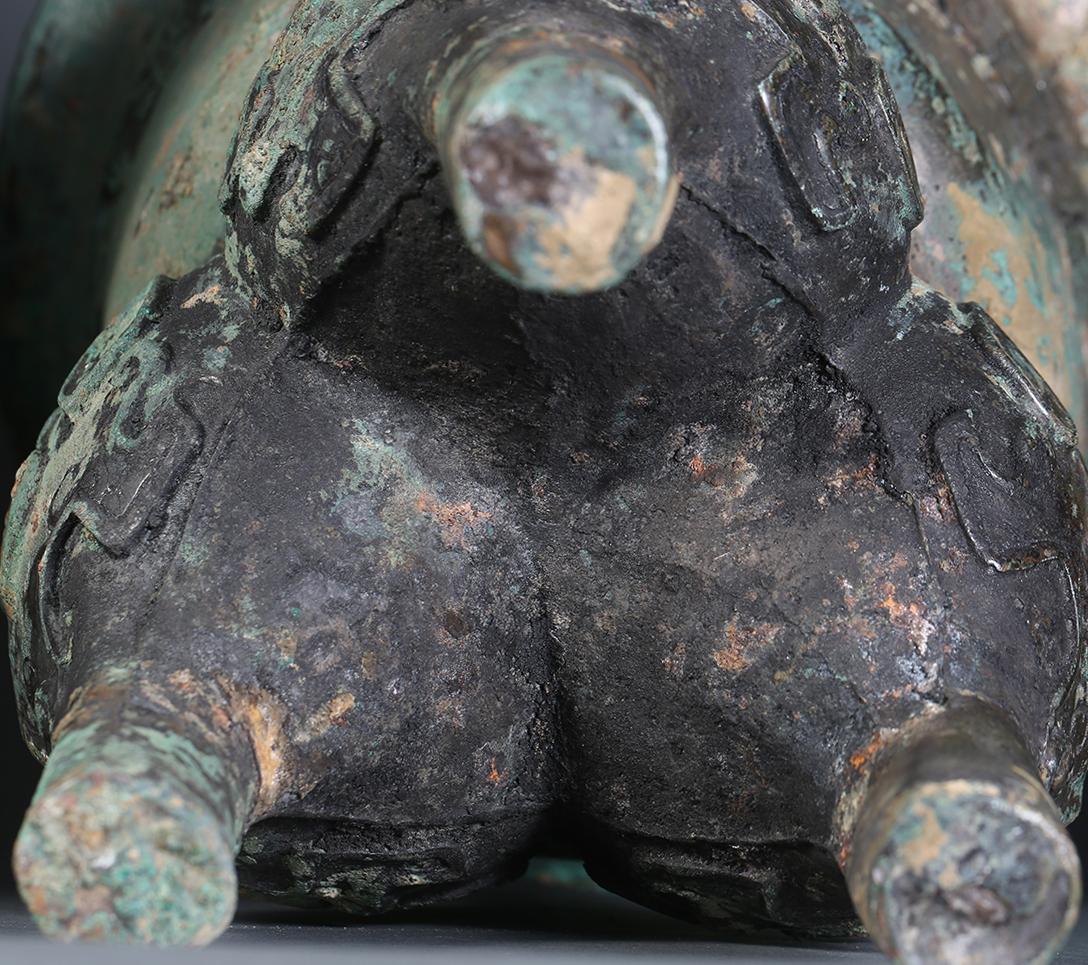

With a wide flared mouth, and a bulbous midsection, the Zun was used as a wine vessel for ritual purposes. Similar in general shape to the gu, the dimensions differ greatly.

These tripod vessels were cooking cauldrons. Some of massive proportions, others of a smaller size. There are either produced in a round form with three legs, or in a rectangular shape with four legs. The example illustrated is inscribed on the interior with the character “good” 好 written in an ancient script. Chinese ritual cooking vessels from this period were often inscribed.

A bowl-shaped ritual bronze, the gui was used to hold food offerings at tomb sites. Typically with a ring base, a fine bowl-shaped body, and a wide mouth.

Not all bronzes were ornately decorated. Looking at the example from the National Museum of China in Beijing we see a piece of a similar date and the same form, but of a substantially simpler design than that of the other sold on iGavel. The Yan was a steamer and the example sold on iGavel retains its original steam tray. The carbon built up on the underside is what you would expect to see from a vessel such as this that had been used.

Highly polished on one side and often cast with intricate decorations on the other, Chinese bronze mirrors have intrigued collectors for more than 4,000 years. Bronze mirrors were in the height of their production in the Han, Tang, and Song Dynasties. Decorated with a variety of themes, it is important to examine these with a slightly more critical eye. Lark Mason Associates sale April 3-19, 2018 contains 12 such mirrors dating from the Han Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty. This mirror is one of these 12 and will be offered with an estimate of $30,000 to $50,000 on iGavel.

Bianzhong is a musical instrument consisting of a set of bells to be played when struck by a mallet. There are bells of various shapes and sizes. An interesting set was discovered in China in the tomb of Marquis Yi (433 BC). This set was subsequently studied for its acoustic characteristics. A set of replicas was created and are currently housed in the Wuhan Museum where they are on occasion played.

The set illustrated here is in the collection of the Shanghai Museum and is the bells of Marquis Su of Jin, who lived during the reign of King Li in the Western Zhou Dynasty.

While these forms serve as a rough guide to the identification of archaic Chinese bronzes, these shapes were repeated throughout the last 4,000 years and are still being repeated today. There are many pieces that look to these forms for inspiration, such as the below 18th-century Chinese cloisonne vase. This piece was not created to deceive, rather, to be its own work of artistry. However, there are many fantastic fakes in the market today and it is best to be cautious.

The permanent collection of the St. Louis Art Museum, Philip Hu as Associate Curator, contains many fine examples of Archaic bronzes.

http://www.slam.org/collections/asian.php

The Nelson Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Senior Curator Colin Mackenzie, boasts some fantastic ancient Chinese bronzes and is well worth a visit.

https://nelson-atkins.org/collection/chinese/

Mirroring China’s Past: Emperors and Their Bronzes

Art Institute of Chicago, IL

Open to May 13, 2018

http://www.artic.edu/exhibition/mirroring-china-s-past-emperors-and-their-bronzes

Ancient Musical Treasures from Central China: Harmony of the Ancients from the Henan Museum

Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix, AZ

Open to May 6, 2018

https://mim.org/galleries/special-exhibitions/ancient-musical-treasures-from-central-china/

Qingbaijing Museum in Chengdu

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201801/10/WS5a55ae84a3102e5b17371dfc_1.html

To view live auctions click here.

Have something like this? Click here to consign.

Further reading:

Jackson Landers, "A Rare Collection of Bronze Age Chinese Bells Tells a Story of Ancient Innovation." Smithsonian.com.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/bronze-age-chinese-bells-tells-story-ancient-innovation-180964459/.

Department of Asian Art, “Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/shzh/hd_shzh.htm

Susan Costello, “An Investigation of Early Chinese Bronze Mirrors at the Harvard University Art Museum” http://cool.conservation-us.org/anagpic/2005pdf/Costello.pdf