Chinese tomb pottery models were made over many thousands of years and models of horses were primarily created during the Han through the Tang dynasty. These models come in a variety of styles and sizes. The largest were from the Sichuan region and can be glazed or unglazed and the finest examples usually are in a Sancai glaze (three color) that usually is in tones described as chestnut, straw, or green. More unusual are those with blue. These glazes were lead-based and have a very fine crackled appearance under a loupe.

Painted pottery horses were modeled in clay, usually in molds which were then painted after removal from the kiln. Some of these models were covered with a cream to white colored ‘slip’ which is a finer clay surface that provides a more finished appearance for the horse and highlights the painted pigments.

Many horses were equipped in the tomb with fabric, horsehair, or other materials to augment the pottery model. These organic materials rarely survive and are almost always missing. Han horses often have large ceramic bodies with separately modeled heads, tails, and legs made of clay or wood, which if wood, are usually missing due to rot.

Horses have heavy clay bodies with slender legs that either are free standing or attached to a rectangular base. If glazed, the glaze will help stabilize the pottery because it provides a protective surface over the ow-fired clay model, repelling moisture. If painted, moisture will wear away the painted decorative elements and even the clay slip. When viewing a pottery horse, do so with an appreciation of the condition of the tomb.

Buried underground, tombs were supported with wood beams and clay-tiled roofs and walls. Over time oxidation could cause heat buildup and fires that would burn through the wood supports. Water seepage would also cause instability to the underground structure. When the structure collapsed or partially collapsed, the fragile pottery objects in the tomb would not withstand contact with a hard surface but would survive a gradual seepage of wet or moist soil slowly entering in and around the objects.

Damage also occurred during the removal of the items from the tomb. Some items came from direct excavations where the earth was removed, and the objects slowly revealed. Others were deep underground and tunnels dug down into the tomb, which in many instances still remained intact. The narrow ‘well’ dug to the tomb would usually be in a small dimension and large pottery objects might have to be purposely and carefully cut to remove in sections. Damages from natural patterns of contact with water and burial are different from those broken out of the tomb which could be purposeful or by accident. In both cases, most tomb pottery models were restored or repaired, and the surface sometimes has a fine random series of minute dark particle pigments that the restorer airbrushed over the damaged areas.

Typical areas of damage are the neck, which is often broken through at the base, the legs usually at the lower part of the leg, ears, and sometimes through the main body. Occasionally elements were missing and in the mix of broken parts in the tomb these were gathered together and then pieced onto the damaged horse. Sometimes these augmentations are very obvious because the proportions are odd. Other times the replacements are not clear, and these can be very difficult to discern from a broken and repaired area using the original material.

Broken and damaged pottery horses are not unusual and most earlyChinese pottery figures are damaged and repaired or restored. The degree of damage is what is important and the location of the damage. Damage in a prominent and very noticeable location is detrimental to the appeal of the object because it changes the way the object is viewed. Damage in areas that are easily concealed is less problematic.

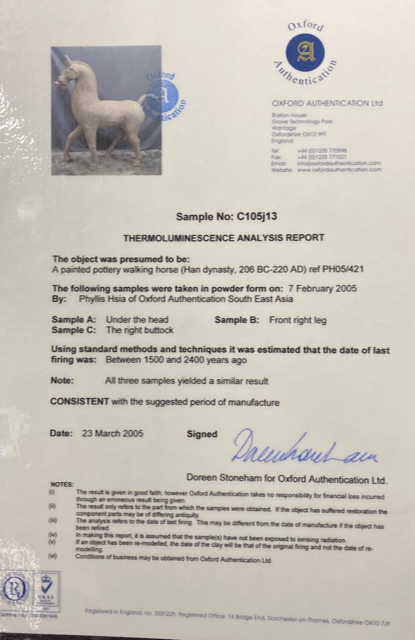

One of the ways that dating is confirmed is through a thermoluminescent test or TL test, and the premier testing organization for art and antiques is Oxford Laboratories in England. Small samples are drilled into the clay body in several locations to verify that that the overall figure is of the same date and origin. Samples are then sent to England, tested and a report issued for the tested object.